Part 1: Majors, Indie or Neither?

In order to decide which is the most suitable path to take the

structure of the industry should be known. The music industry is considered

‘mature’ and a characteristic that leads to this definition is when a market is

dominated by a small number of companies, a structure known as an oligopoly (Hutchinson et al, 2006, p280). As of 28th

September 2012, the four dominant labels (Universal Music Group, EMI, Warner

and Sony BMG) became three when Universal Music Group acquired EMI (UMG, 2012). The major’s take up 74.8% of

the market share, compared to the remaining 25.2% taken by the independent

labels [as of the end of 2011] (Cole, 2012).

This is significant to the bands choice in label for many different

reasons:

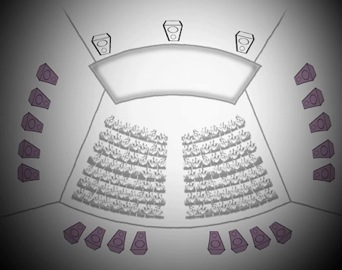

Major and Independent labels often operate similar business structures,

the most important difference being the financial divide. The departments that might

be encountered by a band are as follows:

·

Label President

o Business Affairs

o Accounting

o International

o Artist and Repertoire

o Marketing

§ Artist Relations

§ Creative Services

§ Publicity

§ Radio Promotion

§ Sales and Marketing

(Hutchinson

et al, 2006, p54)

There are many similarities between the way a Major label and an

Independent label are run however one of the main defining differences is that

Major labels tend to own its distribution channel (Hutchinson et al, 2006, p13). This means discounts on the

associated costs across all products under the label for example:

Universal has four main distribution channels

-

Universal Music Distribution (Label

distribution and sales)

-

INgrooves/Fontana (Independent

sales, marketing and distribution)

-

Vivendi Entertainment

(Theatrical releases and home entertainment)

-

Universal Music Distribution Group

Digital (Digital Assets and Mobile)

(Universal, 2012)

To be able to distribute all the company’s products at a discounted

price automatically gives the Major label an advantage. However it is often

common for Independent labels to have an ‘Administered Distribution System’

whereby there is an agreement in place with the distribution arm of one of the

major labels (Hutchinson et al, 2006, p13).

· Record Deal:

There are various deals available with record labels that will have

a direct impact on the income of a band:

· Development Deal:

“Copyright of the recordings is assigned to the record company. Recoupable advances on a track-by-track basis”

· Production Deal:

“The productions company will try and attract a larger record company to license the recordings or sell the contracts to.”

· License Deal

o Exclusive: “Artist or small label retain

copyright, but engage with the resources and expertise of a larger company”

o

Non-Exclusive: “For tracks that will feature as part of a compilation”

Development deals could be beneficial as they would provide a sense

of ‘stability’ over a certain number of years in a multi-album deal. However it

isn’t necessarily a good thing as was the case with the group ‘Jamiroquai’. The

group felt that the record company imposed creative restrictions on them and

that they were more concerned about marketing over the duration of their

8-album deal (Davidson, 2005).

A specialist legal expert should be acquired to check through the

jargon that a contract is usually filled with and ensure that the artist is

getting a fair deal in the circumstances. Contracts usually include the

following sections:

·

Delivery and Release

·

Options

·

Recording Costs

·

Assignment of Copyright

·

Warranties

o Indemnity

·

Additional Clauses

o Video

o Artwork

o Merchandise

o Touring and Tour Costs

·

Termination

o Breaches in Contract

(Morey, 2012)

Contracts can be the make or break or a

band, ‘Queen’ were signed to a production company who ‘sold’ the songs to a

record company and as such the band fell into debt and nearly disbanded (TheHan003, 2012). The predicament has

even been parodied in the cut-scenes from the ‘Guitar Hero III’ video game: A

band duped into signing the contract by false promises (NoBillsOfCrashDamage, 2009)1 and then paying the price

for their naivety (NoBillsOfCrashDamage,

2009)2.

Another key difference is that Independent labels don’t expect to

bring in as much money and as such they may allow you to build on your niche

appeal, rather than looking to convert you into a mainstream act; in essence

they let the artist ply their trade (BBC,

n.d.).

Publishing

Artists usually sign a publishing deal or, for those earning a

significant amount of songwriter royalties, should at least self-publish and

form their own limited company in order to receive the publishers share (AdagioMusic, 2012). An artist will sign

a publishing deal whereby the publishers administer the copyrights and can take

anything from 15% – 50% of the royalties depending on the deal in place. (AdagioMusic, 2012).

The record company will usually pay mechanical royalties, generated

from sources that reproduce the recorded music onto formats such as CD’s, and

Synchronisation license fees, for television and film usage, to the copyright

owner (BMI, 2012). This is where a

publisher will take its cut for administering the copyrights; the exact figure

depends upon the artist and their negotiation position (Jenkins, 2012, email correspondence’). As many labels insist on the

artist signing a publishing deal it can be a disadvantage as they will exploit

their position and charge higher rates whereas the artist is actually in a

better position by controlling their publishing (AdagioMusic, 2012).

Tour Support

Perhaps one of the most overlooked areas in deciding between a Major

or an Independent label is whether there is financial support for tours or live

shows as a part of the deal that is offered. The live music industry is set to

overtake the recorded sector over the next decade if predictions are to be

believed (PRS, 2007). With more

people being attracted to live music events it seems logical that a label would

want to exploit the promotional potential and support the artist financially in

this way. Tour support money is usually advanced to the artist, and is

recoupable, (Hutchinson et al, 2006, p307)

but again referring back to the financial divide between the major’s and the

independent’s it is clear that there is a former has a distinct advantage (Hutchinson et al, 2006, p309). Despite

this it is critical for independent labels to have their artists playing live

events as it forms the very first promotional tool for an artist but also

because “If you’re not touring and not

present in the market, there’s no interest…no retail interest, no consumer

interest, no radio interest, no nothing” (Haley, 2005)

There are other means of attaining funding for tours and shows,

however large funding usually falls at the feet of the established ‘star’. In

2011, R ’n’ B singer Rihanna, signed to ‘Island/Def Jam’ a subsidiary of

Universal (UniversalMusic, 2012), was

sponsored by car manufacturer Renault for her ‘The Loud Tour’ (Renault, 2011). She performed 23 dates

across the UK whilst she also appeared in a television advert for Renault (MusicWeek, 2011). It’s a two-way

promotional device – the artist gains valuable funding for the tour and can

further expand their reach to fans whilst the sponsor gains promotion through

association with a successful artist.

Retaining ownership of

material

Case Study: Alex Day, 23. – Musician and Video blogger, from the UK

There is a strong case for a band to retain ownership of their music

in the current climate that artists find themselves. Having established that, by

signing up to a record label and to a publishing deal, any income from material

is split dependent on the deal agreed and doesn’t necessarily reach the artist

for while (especially when an advance has been paid), there is an incentive to

steer clear of Music industry labels altogether. With the continuing expansion

of social networks and websites such as ‘Youtube’ and ‘Blogger’, it has become

even easier for people (not just artists to reach an audience). Besides the

obvious promotional benefits that labels already exploit, there is an

alternative way in which an aspiring artist or band can manipulate this to

their own advantage whilst bypassing the label system.

Look at the case of artist Alex Day: On the 4th August

2006 he created an account on Youtube, to date it has amassed over 101million

video views (nerimon, 2012). The

importance here is that he started from scratch and built up a fan base through

regular uploads of music and video blogs which has reached in excess of 594,000

subscribers. Having had two ‘top 20’ charting singles within the space of 4

months (OfficialCharts, 2012)2

he had “completely outflanked the labels,

radio, and distributors and went straight to the fans – putting the lion share

of the earnings in the right pocket: his” (Forbes, 2012). There is probably the added revenue of the ‘Youtube

Partnership Programme’, which began operating in Europe in 2008 (BBC, 2008), that pays out money to the

creator from advertising revenues, with the figure received being in direct

relation to the popularity of the videos uploaded. However he earned $200,000

(c. £125,000) from music royalty checks with little or no costs usually

associated with labels.

As a ‘product’ his music succeeds, in a sense, through product

development as:

·

‘There is a market for the

product’.

·

It has appeal.

·

It sufficiently differs from

other products already in the marketplace.

·

It can be produced at an

affordable price.

(Hutchinson et al, 2006)

The obvious problem with bypassing the

major and independent labels is the ties to distribution that prove so

beneficial for artists. However there are alternatives available such as those

used by Day to market his own music. Digital Downloads through online stores

such as iTunes are a way of selling your music independently (iTunes, 2012) without the need for a

physical distributor. The artist may need the services of an external company

in order to ensure content can be uploaded in the correct format (iTunes Connect, 2012) however costs are

greatly reduced as signing up to sell material is free (iTunes, 2012). This is one

example of direct-to-fan sales which include other sites such as Vibedeck

(subscription fee), Topspin (monthly fee), get-ctrl (free except a small share

from sales), Bandcamp (free but 15% share on downloads and 10% on merch). (Nicholls, 2012. Music Industry Lecture,

7/11/2012). Note theses sites act as a place for artists to sell their material

instead of on their own sites as the costs involved make it logical to use an

aggregator (bemuso.com, 2012). Bemuso.com

also show the difference that having a label, which takes a share in the

income, can have on the artist share (bemuso.com,

2012)

DFTBA Records (Don’t Forget To Be Awesome)

was set up by the Green brothers, or ‘VlogBrothers’, and Alan Lastufka (DFTBA, 2012) to assist artists, who have

generated their own audience and created their own brands, with distribution (Green, n.d.). This includes artists like

Alex Day and other British artists like Charlie Mcdonnell (Mcdonnell, 2012) who have built up an audience on their own through

the medium of online video.

Fan funding sites are often a way of

generating vast sums to cover the necessary costs that means an artist can go

through traditional methods without having to get caught up in the trap of

advance payments. Amanda Palmer rose over 1000 times more money than was needed

via a ‘Kickstarter’ campaign (Kickstarter,

2012).

Part 2: Songwriters Agreement

Agreements on songwriting are critical to

maintaining harmony within the group and in some cases the difference between

success and failure. There is an argument for and against who should get what

percentage of the income from a song:

·

If the band contribute various

elements to the songs and are seen to be working in a collaborative manner, it

seems fair that the income should be split evenly.

·

However if there is only one

main songwriter, such as Noel Gallagher was for Oasis (Allmusic, 2012), this could lead to disagreements of who should get

what share of the income. Presumably the band would contribute but the main

credits would feature the lead writer.

In situations such as this, an agreement

between each member is needed to state who shall get what percentage. This can

be verbal or in writing, but preferably in writing as the contract can be

summoned as evidence in the case of any disagreements in court. A notable

example of this is the Spandau Ballet publishing royalties dispute between

songwriter Gary Kemp and the rest of the band. There was a claim that Kemp had

an oral contract in place (since 1980/1981) to pay a share of the publishing

royalties, however these stopped in 1988. A court ruling in 1991 stated that an

oral agreement did not exist and the claim wasn’t valid (Bott, 2012). This underpins the importance of having a good written

agreement that documents the commitment.

There have been situations similar where

whoever wrote the majority of the song would get the full credits. Brian May

stated that ‘Queen’ had that very arrangement in the early days and the extent

didn’t become clear until the songs became hits (TheHan003, 2012).

Conclusion

It all depends upon the artist but

personally, setting up a well-planned ‘Partnership Agreement’ (Allen, 2007, p195) incorporating an

income split based on contribution to the songwriting process would be the best

place to start. In terms of ‘Major, Indie or Neither?’, independent labels are

often more artist than business orientated than the Majors and have more

connections to the industry channels than an artist who retain the copyrights

of their music. Artists such as Adele have proved that you can be more than

successful on an independent label (OfficialCharts,

2012)1. A publishing deal would also be the first choice, with a

bit of research, as any artist with the right attitude for success can’t surely

have the time to deal with their own publishing and be efficient.

References

AdagioMusic (2012) Starting Your Own Record Label and/or Publishing Company: Does An

Artist Need A Publishing Company? [Online] available from: <http://www.adagiomusic.ca/consultingservices/resources/starting_company/>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

Allen, P. (2007) Artist Management – for the music business. Oxford: Focal Press.

Allmusic (2012) Noel Gallagher: biography. [Online] Available from: <http://www.allmusic.com/artist/noel-gallagher-mn0000380158>

[Accessed 4th December 2012].

BBC (n.d.) MAJOR LABELS VS INDIES. [Online] Available from: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/music/introducing/advice/therightdealforyou/majorlabelsvsindies/>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

BBC (2008) YouTubers given share of ad cash. [Online]. Available from: <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/7217479.stm>

[Accessed 28th November 2012].

bemuso.com (2012) Download music costs: online retail cost breakdowns. [Online]

Available from: <http://www.bemuso.com/musicdiy/downloadmusiccosts.html>

[Accessed 2nd December 2012].

BMI (2012) FAQ: What is the difference between performing right royalties,

mechanical royalties and sync royalties? [Online] Available from: <http://www.bmi.com/faq/entry/what_is_the_difference_between_performing_right_royalties_mechanical_r>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

Bott, P. (2012) Lecture 9: Practical Music Law. [Lecture] 14th November

2012. Faculty of Arts, Environment and Technology. Leeds Metropolitan

University.

Cole, M. (2012) Major Labels See Decline In Global Market Share As Independents Grow.

[Online] Available from: <http://www.complex.com/music/2012/05/major-labels-see-decline-in-global-market-share-as-independents-grow>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

Davidson, E. (2005) Mad Hatter. [Online] Available from: <http://www.smh.com.au/news/music/madhatter/2005/11/24/1132703291988.html>

[Accessed 4th December 2012].

DFTBA (2012) The DFTBA Records Family. [Online] Available from: <http://dftba.com/s/4/About-Us.html>

[Accessed 2nd December 2012].

Forbes (2012) Is YouTube and Chart Sensation Alex Day the Future of Music? [Online]

Available from: <http://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanholiday/2012/06/12/is-youtube-and-chart-sensation-alex-day-the-future-of-music/>

[Accessed 28th November 2012].

Green, H. (n.d.) Hank Green – Internet Guy: DFTBA Records. [Online] Available from:

<http://hankgreen.com/> [Accessed 2nd

December 2012].

Haley, D. (2005) Interview

(17/3/2005) from ‘Record Label Marketing’. Oxford: Focal Press

Hutchinson, T., Macy, A., Allen, P. (2006) Record Label Marketing. Oxford: Focal

Press.

Jenkins, E. (2012) Email Correspondence: “Royalty Agreements”. [Email] 6th

December 2012. Boosey & Hawkes

iTunes (2012) Indie Music Signup FAQs. [Online] Available from: <http://www.apple.com/itunes/content-providers/music-faq.html>

[Accessed

2nd December 2012].

iTunes Connect (2012) iTunes Music Aggregators. [Online] Available from: <https://itunesconnect.apple.com/WebObjects/iTunesConnect.woa/wa/displayAggregators?ccTypeId=3>

[Accessed 2nd December 2012].

Kickstarter (2012) Amanda Palmer: The new RECORD, ART BOOK, and TOUR. [Online]

Available from: <http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/amandapalmer/amanda-palmer-the-new-record-art-book-and-tour?ref=search>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

Mcdonnell. C. (2012) About: Bio Quote Sheet. [Online] Available from: <http://charliemcdonnell.com/about/>

[Accessed 3rd December 2012].

Morey, J. (2012) Music Industry Lecture: Week 5. [Lecture] 17th October

2012. Faculty of Arts, Environment and Technology. Leeds Metropolitan

University.

MusicWeek (2011) Rihanna stars in new Renault commercial. [Online] Available from:

<http://www.musicweek.com/news/read/rihanna-stars-in-new-renault-commercial/044856>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

nerimon (2012) Youtube Channel: Alex Day. [Online] Available from: <http://www.youtube.com/user/nerimon>

[Accessed 28th November 2012].

Nicholls, S. (2012) Music Industry Lecture. [Tutorial] 7th November 2012.

Faculty of Arts, Environment and Technology. Leeds Metropolitan University.

1NoBillsOfCrashDamage

(2009) Guitar Hero III - Career movie 3.

[Online Video] Available from: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pigVOmmp65I>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

2NoBillsOfCrashDamage

(2009) Guitar Hero III - Career movie 8.

[Online Video] Available from: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BncMBT2pWbg>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

1OfficialCharts

(2012) Adele. [Online] Available

from: <http://www.officialcharts.com/artist/_/adele/>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

2OfficialCharts

(2012) Alex Day. [Online] Available

from: <http://www.officialcharts.com/artist/_/alex%20day/>

[Accessed 28th November 2012].

PRS (2007) Is live the future of music? [Online] Available from: <http://www.prsformusic.com/creators/news/research/Documents/Pages%20from%20MusicAlly%20Thursday%2029%20November%202007.pdf>

[Accessed 5th December 2012].

Renault (2011) Renault UK To Be Official Sponsor For Rihanna’s The Loud Tour 2011.

[Online] Available from: <http://www.renault.co.uk/about/category/4/newsnumber/5fa3d812-a69e-401d-84b9-b72067199c69/newsitemdisplay.aspx>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].

TheHan003 (2012) Queen Documentary – Days Of Our Lives Part 1/2. [Online Video]

Available from: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PL97F05C8F294D9A4F&v=l7YXd9OAX2U&feature=player_embedded#>

[Accessed 1st December 2012].

UMG (2012) Universal Music Group (UMG) Closes EMI Recorded Music Acquisition.

[Online] Available from: <http://www.universalmusic.com/corporate/detail/2229>

[Accessed 28th November 2012].

Universal (2012) Universal Music Group: Overview. [Online] Available from: <http://www.universalmusic.com/company>

[Accessed 5th December 2012].

UniversalMusic (2012) U.S. Labels. [Online] Available from: <http://www.universalmusic.com/labels>

[Accessed 7th December 2012].